Link To Excerpts from the Beautiful Soundtrack

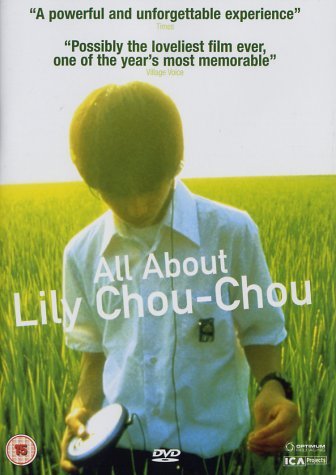

All About Lily Chou-Chou is an interesting piece of filmmaking, partially due to its roots. Director Shunji Iwai would launch an online novel in early 2000, creating a fictional website and posting in the forum section as several different characters. For half a year the site would be regularly updated with members of the public allowed to become part of the ongoing narrative. He would close down the site in late 2000 and start work on the film version, using previously untested Digital Cameras to quickly and concisely film his product before it was released to critical and surprising box office acclaim in 2001. The film would take the constantly evolving narrative of the website and adapt it into a surprisingly bleak and yet elegantly beautiful look at life for modern Japanese schoolchildren.

For anyone who had to deal with bullying, or knew a victim of bullying, All About Lily Chou-Chou will probably be an ordeal. Its lucid, vivid and repellently uncompromising look at social isolation and bullying would probably cut a little too close to the bone. Not that Lily Chou-Chou is the first film to deal with such issues (bullying is after all a fairly generic cinematic trope), but it is rare that the issue is dealt with in a way that is both lyrical and incredibly visceral. Whilst most other films offer a buffer zone of detachment Lily Chou-Chou forces the viewers to feel and relate to its young stars through its near documentary style of film making.

Despite this documentary stylisation film is stunning to look at, its colour palette and design ethos giving vibrancy to an altogether rather bleak film. Shot entirely on DV cameras the film has a sort of ethereal quality, a point reinforced by the hazy and often dreamlike narrative. If anything Lily Chou-Chou feels like a film which is suffering from post traumatic stress, its recollection of scenes hazy and confused, events cutting off and merging haphazardly. As such we are largely only offered glimpses of the story; key events delivered without context which all build up to create the central arc of the film. A contributing factor to this haphazardness is the way the chronology in the film works, or to be more honest doesn’t.

All About Lily Chou-Chou follows two Japanese schoolboys as they leave Junior School, go on a summer vacation and attend the first year of High School. Yuichi is something of an introvert, devoting his time to the running of his fansite and listening to the music of Lily Chou-Chou. He has a few friends at school which is more than can be said for Hoshino, the academic star of his year whose success has ostracised him from the rest of his peers. The film opens in high school with Hoshino having already turned on all around him and set himself up as a vicious and brutal bully. His relationship with Yuichi is never fully explained until about thirty minutes into the film when the narrative doubles back on itself to examine the previous year’s events.

In a lot of other films the boys bonding and eventual trip to a sunny locale (in this case Okinawa) would be handled with a light and breezy touch, the slight of hand to prepare you for the sucker punch of the next two acts. What Lily Chou-Chou does is cast a shadow over these moments of exuberance; we know that Hoshino is going to turn out bad. But by looking at these happier times with foreknowledge of his present situation everything becomes a little darker, a pall is cast over every event and the viewer finds themselves searching for links as to Hoshino’s change in behaviour.

In a lot of other films the boys bonding and eventual trip to a sunny locale (in this case Okinawa) would be handled with a light and breezy touch, the slight of hand to prepare you for the sucker punch of the next two acts. What Lily Chou-Chou does is cast a shadow over these moments of exuberance; we know that Hoshino is going to turn out bad. But by looking at these happier times with foreknowledge of his present situation everything becomes a little darker, a pall is cast over every event and the viewer finds themselves searching for links as to Hoshino’s change in behaviour.

Our first encounter with Yuichi is as a miscreant and then as a victim, our first encounter with Hoshino is as a victim and then a miscreant. The establishing moment for Hoshino is a speech he is forced to read on behalf of his classmates explaining their hopes and aspirations for high school. You can see the duality immediately, the pride at being chosen for this honour conflicting with his persistent knowledge of his classmate’s hatred.

This trip to Okinawa during the school holidays is funded by the aftermath of a petty theft, the boys descending on a robbery and sprinting away with the loot they find. It is Hoshino who makes the first move and invariably secures the money for the boys and it is another layer added to the character. He is already acting out by this point, but without the context of the schoolyard or his later violence. It is only during the trip to Okinawa and a series of near fatal accidents that Hoshino truly withdraws from the group. His near Shakespearean fall into isolation and near madness is juxtaposed against the stories of those whom he abuses and allows to be abused. Indeed, the last hour of the film is so shocking because of the fact that Hoshino is so calculating. His actions are carried out with a cool, detached, malice and his crimes become more and more unspeakable.

A film which started off as an average treatise on school life suddenly descending into a brutal, nihilistic, vision of a schoolboy kingpin who blackmails his schoolmates into prostitution, organises a brutal gang rape and ritually humiliates one of his closest friends. Indeed Hoshino’s first two acts aren’t particularly violent but demonstrate a cruelty and malice that is utterly disturbing. We first see him betray Yuichi (setting his gang on his former friend and destroying his prized CD and CD player) and then we see him assert dominance over the school bully by stripping him of his pride. He doesn’t particularly harm the bully, he just makes a mockery of him in a detached and sociopathic way.

A film which started off as an average treatise on school life suddenly descending into a brutal, nihilistic, vision of a schoolboy kingpin who blackmails his schoolmates into prostitution, organises a brutal gang rape and ritually humiliates one of his closest friends. Indeed Hoshino’s first two acts aren’t particularly violent but demonstrate a cruelty and malice that is utterly disturbing. We first see him betray Yuichi (setting his gang on his former friend and destroying his prized CD and CD player) and then we see him assert dominance over the school bully by stripping him of his pride. He doesn’t particularly harm the bully, he just makes a mockery of him in a detached and sociopathic way.

His snapping of Yuichi’s copy of the new Lily Chou-Chou CD is perhaps far more significant than any other action in the film. It’s a severance of ties between him and his old friend and also a pollution of the ‘ether’ a spiritual energy which Yuichi and Hoshino talk about on their website. The major indication of the extent of this action is the fact that the near continuous soundtrack is ominously missing for a few minutes after this action. In fact it doesn’t return until the film goes back into itself for the flashback. Music plays such a large and vital part of the film that its sudden absence feels almost like an assault and its conspicuous absence suggests the destruction of purity far better than anything else in the film.

At its core All About Lily Chou-Chou plays broadly with the corruption of innocence idea. The corruption of the Ether (a term used several times in the film) a pretty apt metaphor for the corruption of innocence taking place within the children’s lives. Music is the only escape Yuichi has from his tormentors and the only way he can truly connect with his fellow victims. The text message excerpts from his website explain how easily people fall into the lure and escape of the Ether and the final scenes go a long way to corrupting even this last bastion. Indeed Yuichi is not really a victim in a traditional sense, only suffering one physical abuse at the hands of Hoshino’s gang. More than anything else the damage is done by how he is forced to intergrate into Hoshino’s ever expanding gang, given the menial task of watching over the schoolgirl Hoshino has turned into a prostitute.

The film offers no real answers to the problems of bullying and to expect it to would be rather moronic. What it does is paint a real picture of what it is like to be a victim of a bully and how innocuous and random their dislike can be. The overall message is rather distressing; the film seems to revel in unilateral action as the only way to fight against bullying. As such suicide, self sacrifice, and murder are the only solutions the victims are left with. Whilst the film seems to drift toward melodrama at points, the rape scene and the fate of a girl doomed to be a child escort both feel perhaps a little detached from the general narrative, the effect of the Digital Photography always grounds it at least in a facsimile of reality.

That is the odd dichotomy at work in All About Lily Chou-Chou its ethereal elegance matched with material that is indicting in its reality. It is a tale that is both supremely stylised and at times hyper real. It is a film that is utterly shocking and morally depressing but that is also lyrically beautiful and bursting with colour and vitality. Every technical aspect is remarkably polished even the fictional score by Lily Chou-Chou is the kind of music that is enrapturing and alluring and it all works to make the impact of the film even more brutal.